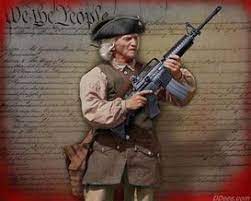

Buying an AR-15 in 1791

The uniquely American controversy over gun control has raged on and off for over twenty years since the carnage at Columbine High School in April, 1999. It would be difficult to find someone now in the United States who does not hold a firmly entrenched position on guns, even if that position is in the middle. The right wants no laws at any level that restrict the sale of guns. The left wants at least a near total ban on the sale of guns. The middle accepts a gun industry for reasons of sport or protection, but wants common-sense restrictions. For the past twenty years, the right’s position on guns has comprised the unassailable law of the land.

Regardless of one’s position, the controversy focuses on the Second Amendment (known herein as “A2”) to the Constitution of the United States, which in its entirety is shown as follows:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

Never have so few words meant so many different things to so many people. Probably a majority of U.S. citizens believe the Second Amendment grants a right to all Americans to privately own an assortment of arms for a variety of uses into perpetuity, although this group would have varying definitions of the word “arms,” what the variety of uses should include, and if or how such ownership should be curtailed. However, there is a minority of Americans who believe that the Second Amendment grants no such right to private ownership of arms and, even if it did grant such ownership in 1791, the context in which it was granted has long since ceased to exist, which makes the right obsolete.

But before we dive into the heart of those disagreements let’s first consider a short history of A2 and then a short primer on the grammar of A2.

The History

The Continental Congress voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the date most Americans consider as the birth of the United States. The Revolutionary War between the colonies and Great Britain actually began in 1775 and ended on September 3, 1783 at the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The war however had unofficially ended in 1781 when the British surrendered at Yorktown, or some would say later in 1782 when Britain withdrew the last of its troops from South Carolina. We can take any of these dates as the birth of our nation: 1776, 1781, 1782, or 1783. Take your pick.

What is germane to our discussion is that the U.S. first formed a continental army in 1775 and used that army to fight for another seven years to expel the British army. After winning the war, the colonial leaders got down to the serious business of forming the documents which would provide the foundation around which the U.S. government would be constructed. The U.S. Constitution was signed on September 17, 1787, roughly eleven years after the Declaration of Independence and four years after the official end of the War.

Article V of the Constitution lays out a framework by which the original 1787 document could be altered, or amended. Article V states that the Constitution could be changed in one of two ways: 1) two-thirds of both Houses of Congress can propose amendments; or 2) two thirds of the state legislatures can propose amendments. Amendments can only be ratified through a vote of three-fourths of the State Legislatures or three-fourths of the state conventions called by those legislatures.

As would be expected, the original Constitution would experience frequent edits, or amendments. The first batch of such proposed amendments was sent to the States for approval in 1789 and contained twelve proposed amendments to the Constitution. Only ten of these amendments were ratified by ¾ of the States and became known as “The Bill of Rights,” which was finally ratified on December 15, 1791.

The second of those amendments, or “Rights,” has to do with….well, we’re not sure what it has to do with. Evidently, the U.S. used to be sure what A2 said, but clearly, we no longer agree on what right is enshrined in the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution which became part of the Constitution four years after the original document was signed. The meaning of A2 is the topic of this post.

A Lesson in Grammar

Let’s look at the wording of A2, that most controversial sentence in the Bill of Rights passed on December 15, 1791.

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

Of all the interpretations and arguments over the meaning of this Right, one thing is incontrovertible: it is poorly written. There is a comma splice between “…free state” and “the right of…” which undermines the purpose of the phrase “the right of the people to keep and bear arms.” For the final clause to make sense, some people would re-write the whole sentence as follows:

By replacing the comma splice with the coordinating conjunction “and,” the sentence appears to flow a bit better. But the correction does not improve the meaning of the sentence. Is a well-regulated militia necessary to a right of the people to keep and bear arms? Maybe, if you’re worried that a lot of armed people may rebel and you therefore need an army to suppress a rebellion. But this interpretation presupposes that the right to bear arms had already been established in the Constitution, and in fact, it had not.

Let’s try another rewording:

“Being necessary to the security of a free state, a well regulated Militia and the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

This presentation helps to correct both the grammar and the diction. This sentence would be interpreted as meaning the Founding Fathers were primarily worried about national security in 1791, as would have been prudent since Britain still considered itself a far superior military power to the U.S. and it therefore would be wise for the U.S. to be concerned about Great Britain’s army returning for a second try (as they did 21 years later). In this context, the Founding Fathers would be saying that to protect ourselves we need standing militias and we need people to populate those militias – people who have guns.

Keep this context in mind. Before we return to it, let’s put out there the wording of the A2 which is prevalent in the United States in 2022:

“The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

Modern America, especially over the past twenty years, has ignored the first two phrases in A2. Modern day Americans and most of today’s local, state, and federal governments conceive of A2 as a guarantee that all Americans have the right to buy weapons without any interference or with minimal interference from any governmental authority. Period. End of story. No further discussion is necessary. It says that in clear language in the Bill of Rights which is incorporated into the U.S. Constitution.

The erasing of the first thirteen words of A2 was formalized by the Supreme Court of the United States in The District of Columbia vs. Heller, a 2008 casein which the majority of Justices ruled for the first time in U.S. history on the meaning of A2, deciding that it meant private citizens had a right to own guns separate from any connection to a militia or national security. It is important to know that this was the first time that this interpretation of A2 was ever made by a branch of the U.S. government, and it took 217 years to get there. The decision was written by Justice Antonin Scalia, a conservative Jurist known for his “textualist” approach to the Constitution, which instructs that the Constitution means what a reasonable person would understand the words of the Constitution to mean. Without getting off on a tangent, I think Antonin Scalia really practiced Scaliaism, which teaches that the Constitution means what Antonin Scalia wants it to mean.

Considering the fact that A2 was so poorly written, it was only a matter of time before its interpretations went off the rails.

But to make Scalia’s interpretation one must ignore the troublesome and poorly worded phraseology that precedes “the right of the people…” What were the Fathers thinking about when they parsed this “right” within the context of a “well-regulated Militia” and “the security of a free state?”

More History

To understand what they were thinking, more 1791 context is necessary. The United States, less than ten years after winning the war, had a weak federal government. In fact, many of the Founding Fathers had no intention of forming a strong federal system. There was no effective standing federal army. The systems by which the three branches of government would be funded were in their infancy. Most of the population still thought of themselves as being citizens of the state they lived in (Virginia, New York, Massachusetts, etc.) and not a citizen of the United States. The Fathers who wanted a strong federal system knew that such a reality would have to evolve over time.

In the context of national security, the immediate issue was how the new country would defend itself in the case of an attack. As stated, many representatives in the Second Continental Congress did not want a strong federal government in any form, let alone an army. Raising funds (or borrowing them) to build a standing navy and land force to withstand an attack was not feasible. They were well aware of the fact that Britain’s army failed to win the war for four reasons: 1) France allied itself with the colonies; 2) the lack of infrastructure in the colonies made it extremely difficult for Britain to leverage its superior numbers and equipment; 3) disease and exposure to severe weather crippled the invading force (of the approximate 24,000 British soldiers who died in the war, about 17,000 died from disease or exposure); and 4) the Continental army, which is probably a distant 4th in the number of reasons Britain lost the war. Without seeming unpatriotic it would be more accurate to say that the Colonies didn’t win the Revolutionary War; rather, the Colonies failed to lose the Revolutionary War.

In 1791 therefore, Congress had a logistical problem. A standing army of say, 20,000 men would require 20,000 muskets, 20,000 uniforms, 60,000 meals per day every day, housing, transportation equipment, etc. The Continental army had been reduced to 80 men after the War ended in 1783. In 1787, Congress organized the first federal army of 700 men gathered from four state militias which became the U.S. official army a few years later. So they had a problem. The United States was defenseless, save for help from Mother Nature and/or the French. They had to do something.

Defense of the country was formalized with two separate acts of Congress in 1792. The “First Militia Act of 1792” gave the U.S. President the authority to call on the state militias if the country was attacked. The “Second Militia Act of 1792” required state militias to be formed (if they weren’t already) and for the conscription of every male between the age of 18 to 45. We don’t speak about these Acts of Congress today because they were laws – not attached to the Constitution. But they speak volumes about the context of the Bill of Rights and how a reasonable person should understand Congress’s intentions in 1791, less than a year earlier.

Here is the important part and the reason for this history lesson – the Second Militia Act of 1792 required conscripts to equip themselves with “musket, bayonet, belt, two spare flints, a box to contain 24 cartridges, a knapsack, a powder horn, ¼ pound of gunpowder, and 20 rifle balls.”

Note that these were state militias, similar to the current day national guard. These men went about their lives, farming, lawyering, milling, etc. They were not professional soldiers. But they were required to arm themselves! A2 and the laws passed less than twelve months later, were not so much an establishment of a right as it was an establishment of a requirement, an unavoidable requirement as part of the national security of the United States at the time.

This is the context in which the Second Amendment was written. The U.S. government had no money. The U.S. government had no army. The U.S. government was vulnerable. Organizing a national defense could only be realistically done on the local level. Basically, individual citizens were charged with the responsibility of arming themselves; if called to war, the government would hopefully assume the logistical responsibility of re-arming them, but the system had to be a free first-responder effort. Citizens were to bear the cost of arming themselves and carrying those self-owned weapons with them into war.

This made complete sense at the time because most men already had much if not all of the required equipment. In 1791, there were few if any effective police or constable departments, certainly none that could be relied on in the case of an emergency. Men relied on hunting for daily meals, they relied on guns to protect themselves against crime, they relied on guns in the case of an animal attack. In 1791, guns were not optional. They were a required household tool.

In other words, the government did not want to infringe on an individual’s right to bear arms because the government was at the same time requiring individuals to bear arms as the sole source of national defense.

A2 in 2022

Fast forward 232 years. As discussed above, because of incoherent wording, or because of convenience, we’ve essentially discarded the first two phrases in the Second Amendment. We’re not sure what the bit about the Militia means, nor the bit about the security of a free state, so we’ve discarded it. We want A2 to be about the final phrase so that’s what it is. If you’ve never read the Bill of Rights you would assume, from listening to the nation’s leaders, that A2 reads “The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” If you actually took the time to read the Bill of Rights and the actual Second Amendment (or, God forbid, the entire Constitution or maybe a chapter in a history book), you’d say to yourself, “How did we get here?”

It is the height of intellectual dishonesty to think that the Founding Fathers wrote A2 because they intended 18-year-old kids to one day have the ability to go into a gun store and buy a weapon that can fire 30-40 bullets in seconds. It is the height of intellectual dishonesty to believe that the founding fathers, after seeing the size and power of our modern military and police forces would still mandate a right to keep and bear arms. It is the height of intellectual dishonesty to think that the founding fathers, after seeing a population of 325 million owning 400 million guns and 500 mass shootings per year would still insist on a right to keep and bear arms.

I have never owned a gun. I’ve never even held a gun. Yet, as a U.S. citizen, I’ve spent more of my hard-earned money on weaponry than the overwhelming majority of human beings ever born. I spend $700-$800 billion every year, year in and year out, to equip the U.S. army, navy, air force, marines, and coast guard. I spend more money to equip my Pennsylvania state police and national guard. I spend even more of my money to equip my local police department. I spend that money willingly, and without hesitation. Without ever having bought a gun, I am armed to an almost inconceivable level. So why do I need a personal gun? If the U.S. is attacked, I send men and women to eliminate the threat. If my property is accosted (as it was years ago when I personally experienced a home invasion), I dial 911 and the men whom I have equipped arrive in minutes if not seconds (as they did on that night). 1791 and all the historical context in which A2 was written is long, long gone. To ignore this fact is dishonest and duplicitous.

Modern history is witness to a continuing carnage: Columbine, Sandy Hook, Virginia Tech, MSD High School, Aurora, Pulse, Buffalo, Uvalde, and the hundreds of similar incidents, all done in the name of what Americans no longer even argue – a second amendment right to bear arms.

I suggest the Second Amendment grants no such unchecked right. In the presence of the largest military in human history and several layers of local police protection, U.S. citizens’ right to bear arms should be granted only in limited circumstances such as sport or protection, and even in these cases the number and type of arms should be limited and the licensing should be pervasive.

- John Barton

Leave a reply to OG Cancel reply