When I went to business school over 40 years ago, I was taught the same thing about personal investing that B-school students learned before me and the same thing they’ve learned since. It’s the same thing that many wealth advisors tell their young clients: if you invest in large-cap corporate stocks (say, an S&P 500 Index Fund) each year, and never deviate from your plan, you will provide an adequate retirement fund for yourself. It’s a can’t miss proposition. I actually recall sitting down in the personnel department of my first real job when I was 23 years old. I had declined to participate in the 401K plan and the advisor begged me to reconsider. I recall her saying, “It’s critical to invest while you’re younger since that money has more time to grow; even a small annual investment helps.” My replay: “With all due respect, my annual salary is $17,000. After paying for rent and beer, I’ll be lucky to have anything left over to buy food.”

Of course, she was right. The common wisdom is that, on average, an investment in the equities market will generate an annual after-tax return of 8.0% to 10.0% over the long term. Individual years may vary greatly. The markets have had disastrous periods like the great recession of 2008-09, and virtually the entire decade between 1929 and World War II. But the markets have also had stellar years, like the late 1990s and between 2010 and 2020. If you stay the course, taking the good with the bad, you will, by the time you reach 65, provide enough of a retirement account to support yourself after you leave the work world.

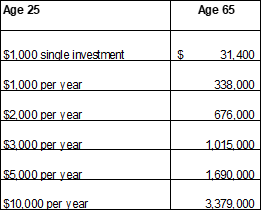

Consider the mathematics of this common wisdom. If you buy a one-time $1,000 investment in the market at age 25, and earn a 9.0% annual return (and do nothing else), that single investment will turn into $31,410 when you are 65. If you invest $1,000 every year between age 25 and 65 and earn a 9.0% return, you’ll have a nest egg of $338,000 when you’re 65. As the chart below shows, the numbers go up from there.

Note that the above projections are based on investing after-tax dollars. If you invest in a traditional IRA account (or a similar vehicle), you would be investing pre-tax dollars, meaning you’ll have to pay income taxes on the other end. So, for example, if you invest $3,000 every year between 25 and 65 in a traditional IRA or a 401K plan, yes, you’ll have $1,015,000 at age 65, but you will have to pay income tax on that income when you take it out in retirement.

There have always been problems with this investment advice. Being young is expensive. Besides the high cost of beer, there are start-up costs with being twenty or thirty-something, especially with married couples. Paying off college loans, buying houses, cars, insurance, appliances, and furniture is bad enough. When you add children to the mix, budgets suddenly explode. The idea of having $5,000 or $10,000 lying around at the end of the year to invest in stocks would be a hardship for most couples. Older people, like my personnel advisor when I was 23, push back on that. They tell you to force yourself to put away at least $1,000 or $2,000 per year now and make up for lost time later on. It turns out that that was sound advice. In 1983. But is it sound advice for a young person in 2024?

If you asked me that question as late as a year ago, I would have said yes. Absolutely yes. Now I have strong and growing misgivings. I think the common wisdom on investing may need to be revisited.

Research has been mounting over the past decade that suggests the assumptions which support the common wisdom on long-term investing are increasingly invalid. This paper focuses on what the assumptions are, why researchers are questioning their validity, and what alternatives an investor can take.

The Assumptions Behind Long-Term Investing

Financial analysts are in the business of quantify two variables: 1) growth; and 2) risk. Growth is easy to understand (though difficult to predict). Growth in stock returns consists of two things: 1) increases in a stock’s price; and 2) dividends paid on the stock. Risk is difficult to understand and difficult to measure. Put simply, risk is the likelihood that an investor’s assumptions about stock returns in the future (i.e. growth) will actually occur.

When an investment advisor tells you that you can count on an annual return of 9.0% over the next 40 years, he/she is making assumptions about both growth and risk. Stock investing wisdom is based on observations of stock market activity over the last 100 years (actually, 98 years to be exact as of 2024) and the assumption that the next 100 years will – on average – be a repeat of the last 100 years. Investment professionals assume that the last 100 years is the best proxy we have for what will happen over the next 100 years. Total after-tax returns on large-cap stocks over the past 100 years on average fall into the 8.0% to 10.0% range. If your great-grandfather invested $1,000 in a portfolio of large-cap stocks in 1924 and bequeathed that single investment to you, you would have over $5.5 million today. Having said that, $1,000 in 1924 was not a small investment. Your great-grandfather could have bought a modest home with $1,000 to $2,000 in 1924.

The logic that the past is prologue for the future cannot be dismissed easily. Lots and lots of bad and terrible things have happened over the last century, as have lots and lots of great things. Since 1926 when robust data on the U.S. stock markets started to be collected, our society has suffered minor and major depressions, wars, pandemics, periods of inflation, earthquakes, tidal waves, floods, tornadoes, and hurricanes. We even had a major volcano eruption in 1980 (Mount St. Helens). We have also enjoyed long periods of stunning expansions, periods of almost unimaginable scientific and technological advancement, and, for the last 40 years, negligible inflation. The logic is as follows: All these bad things and good things represent the spectrum of possible events in the future. If fewer of the bad things had happened, the average historical returns might have been above 9.0 percent. If fewer of the good things had happened, the returns would have been smaller. But they didn’t. The good and the bad events combined to give us an average 9.0% return on a large-cap corporate portfolio of stocks. The reasoning is that we should expect the same mix of good and bad things over the next 100 years.

What Went Wrong With the Assumptions?

Several economic trends threaten to undermine the assumption that historic economic events are the best proxy for future ones. These include price to earnings (P/E) ratios, corporate tax rates, interest rates, and the rise of passive investing. Let’s take them one at a time.

P/E Ratios

As the name suggests, P/E ratios express a company’s value in terms of its earnings. A P/E ratio of 15.0x means that the Company’s value is trading at 15 times its annual net income. So, if a company made $1.0 million last year, you would pay $15.0 million to buy all the company’s equity.

P/Es are also measured and published in terms of the entire stock market. Analysts consult the market P/E ratio as one indication of whether the market is underpriced or overpriced. Historically, P/E ratios for the entire market have averaged in the high teens. Note that market P/E ratios, like stock prices, are a short-term metric, meaning that they will change, sometimes significantly, year to year and even month to month.

Right now, the market P/E ratio for the S&P 500 stock index is about 25.0x, which is nearly 7-8 points above the average. All that means is that the current stock market overall is probably overpriced. Warren Buffett, the legendary investor, is currently sitting on nearly $170 billion in cash. Why? Because he thinks most of the stocks in which he could invest this cash are overpriced, so he’s sitting on the sidelines until prices come down. History suggests that prices will decline.

What are we actually doing when we pay 25.0 times earnings for a stock? Assume a company is earning $10.00 per share. That means that if it has a P/E ratio of 25.0x, you would pay $250.00 for one share. That may seem like a high price from the perspective of what is called a payback analysis, which assesses the number of years it takes for an investor to get back what he paid for an asset. In this case, the payback would be 25 years assuming the company earned $10.0/share each year into the future. It would only be in year 26 that the investor in this case would start earning a positive return.

Obviously, it makes no sense to wait 26 years to begin earning a return on your money. So why is the stock market trading at a P/E ratio of 25.0x? The answer is expected growth. Lots of expected growth. The market is betting that the stock’s earnings will not be $10.00 per share next year. It will grow to $13.00, then $15.00 the year after, then $17.00, and so on. With growth, the payback period is much shorter. Earnings growth can be inflationary and it can be organic. Organic growth can come from an expanded market or market penetration. Companies can also grow by acquiring other companies. All these factors can combine to make a payback period much, much shorter.

For a market P/E ratio as high as 25.0x, the market is expecting high long-term growth. However, long-term growth into perpetuity cannot be higher than population growth plus inflation, which right now is a combined metric of 3.5% to 4.0%. With a P/E ratio this high, is the market counting on growth rates that are too high?

The answer is yeah, probably. See below for why.

Corporate tax rates

Corporate profits increased by 2.0 percent on average each year between 1962 and 1989 and then grew by 4.0 percent per year on average between 1990 and 2019. The question is whether or not corporations can repeat this growth over the next 60 years. If we assume that we will earn that 9.0 percent annual return on our stock investments, corporations would need to achieve at least a 2.0 to 4.0 growth in profits.

Two events in the U.S. economy over this 60-year history suggest that it will be difficult to repeat these historical growth rates.

First, a large part of the profitability growth came from a decline in the U.S. corporate federal income tax rates, which dropped by 60.0% in the last thirty years. The corporate income tax rate dropped from 52.0% in 1952 to 38.0% in 1993 and to 21.0% currently. A sea change in tax rates came in the 1980s during the Reagan and Bush presidential administrations when both corporate and personal tax rates declined from the 40.0 to 55.0% range to the 30.0 to 35.0% range. More recently, corporate rates dropped again under the Trump administration to 21.0 percent, far lower than where they had ever been in history.[1]

Obviously, this decline in tax rates is partially responsible for the historical growth in corporate profits. For the assumption that the historical 9.0% annual investment return will recur over the next 40 years, we have to ask, will the federal government make the same reduction in tax rates between 2024 and 2064?

For several reasons, the answer is no. First and foremost, the federal government would have to eradicate corporate taxes completely to get a similar corporate tax reduction over the next 40 years. Second, eventually the federal government will need to address several costly problems, including the federal deficit ($34.0 trillion and growing every year), social security obligations (social security is currently forecast to go bankrupt in 2034), and environmental liabilities (an incalculable cost). Each of these will require either a substantive increase in tax rates or, in the absence of higher taxes, a profoundly diminished standard of life in the U.S. The inescapable conclusion is that a major cause of the growth in corporate profits over the past 60 years not only will not recur, it will reverse.

Interest Rates

There is a similar story with interest rates. I assume you’ve read several stories over the past two years about low inflation rates which ranged in the 1.0 to 2.5% range between 1989 and 2021. As a result of the pandemic and its aftermath, inflation soared to 9.1% by June of 2022. Lower interest rates mean lower interest expense to corporations, and higher profits. The reverse is true – when interest rates rise, corporate profits decline.

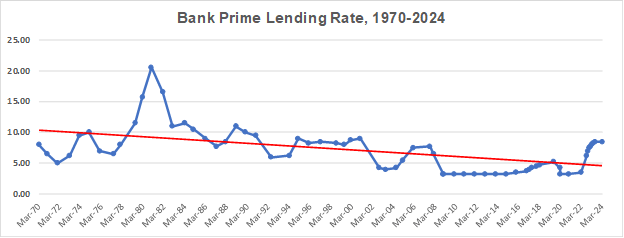

When inflation surges, the Federal Reserve Bank raises interest rates to try to slow down the economy. The Federal Reserve Bank raised interest rates steadily during 2022 and 2023. By raising interest rates, lending becomes more costly to companies, which hinders economic expansion, thus theoretically cooling off the economy and lowering inflation. As the graph below shows, lending rates to most corporations ranged between 7.0% and 20.0% between the mid-1970s and 2008.

[1] As an aside, the national deficit, which currently stands at $34.0 trillion, went into hyperspace during the 1980s when both corporate and personal tax rates began their precipitous decline. Coincidence? No, not at all. Over the last 40 years we’ve collected far less tax revenues than we should have been collecting.

After the 2008 recession, rates dropped below 5.0 percent, where they stayed until after the pandemic in 2022. The low lending rates were a boon to corporations which borrowed money at historically cheap prices. Lower lending rates meant lower interest expense, which meant higher corporate profits.

The decline in interest expense and higher profitability was another factor which contributed to the growth in profits, especially in the period 1989 to 2019 which, as discussed above, saw corporate profits grow by 4.0% per year. As of April, 2024, the prime lending rate is back at 8.5%. Interest expense is higher. Inflation declined to 3.5%, but is rising again. Economists believe that the Federal Reserve may have to return to a cycle of interest rate increases to get inflation down to a desired level of 2.0%.

The trendline which caused the growth in profits (see the declining trendline above) will not recur over the next few decades. Like tax rates, lending rates will not decline to below 1.0% per year (or if they do, we’ll likely have a whole different set of problems).

The point is that these factors which caused the growth in corporate profits which contributed greatly to the 9.0 annual return that stock portfolios generated in the past will not recur over the next 40 years. So why are we assuming an 8.0% to 10.0% annual growth in our investment planning?

Passive Investing

Sadly, there is a whole other issue that market analysts fear may have contributed to the market’s rise over the last 40 years. That is passive investing.

Economists believe that the stock market is “efficient.” This means that stock prices incorporate all available information in a relatively short period of time. For this to happen, the assumption is that all investors, or all investors’ stock brokers, are constantly monitoring all economic, financial, social, and political events and how these events will affect their investments. Investors relentlessly look for buy and sell opportunities based on the latest information. Each company’s stock price is therefore the fair market price given everything that is known at a given time.

Over the past 40 years the rise of mutual fund investing has worked against this idea of an efficient market. Mutual funds are portfolios of stock investments that mirror an exchange (e.g. the S&P 500, the Nasdaq, etc.) or an industry segment within an exchange. When an investor puts his or her money into an S&P 500 index fund, he or she is investing in all 500 companies. It’s the same with all the other mutual funds, even though they may be tailored a bit more specifically to segments within the market. The investments are made through an investment house (Vanguard, Fidelity, etc.) but no one really monitors them. In short, the investment is passive because there is no analysis like what is described above; there is no “constant monitoring of events.” This is what is called passive investing.

The theory is that one of the causes of the market’s rise over the past 45 years is passive investing. Before 1980, few people ever heard of mutual funds. Vanguard was responsible for bringing them into the mainstream during the 1980s. Now, over 60% of Americans are invested in them, to the tune of $11 trillion. Over 50.0% of the total assets under management in the U.S. stock market were passive investments as of December, 2023.

In a sense, this is dumb money since people are investing and forgetting. When so much dumb money chases stocks, stock prices increase. They increase whether or not the stock warrants a higher price. Imagine a grocery store that wants to set a price for chicken. The store manager learns that a massive number of shoppers are going to come to the store to buy chicken no matter how much it costs. They’ve been told to buy chicken by their investment advisors. So they buy without researching how much it should cost, whether they can buy it cheaper elsewhere, etc. Clearly, the store manager is going to raise the price of his chicken.

Therefore, as you put more money into a mutual fund, one of the things you might be betting on is that other people will continue to put their dumb money in as well. Since the investments are not made on any kind of analysis, it’s really a game of musical chairs. Eventually, the music will stop, hopefully long after we’ve pulled our money out, but maybe not.

The Pessimist’s Summary

These key factors which drove stock prices higher and higher over the past century almost certainly won’t continue to drive prices up over the next 50 years. Some of them, like lower corporate tax rates, can’t. Others, like lower interest rates and passive investing are extremely unlikely to continue their effect on stock prices. Therefore, the conclusion should be that the past is not prologue for the future. We don’t necessarily know what the future will be, but if the market actually does provide a 9.0% annual return in the next 50 years, it will have to come from some new economic phenomenon.

An Alternative View

For every economic argument, there’s always a contrary view. Economics is not a real science that can reduce the natural world to equations, laws, and algorithms; it’s a behavioral science, meaning that it is affected by human behavior. Since economic equations are affected by human behavior you will often hear economists introduce their equations with the statement, “All else remaining equal….” That preface can be restated, “if past human behavior and conditions remain the same, then….” The problem is that human behavior is not a constant. It is always changing.

The essay above argues that you should not invest in the stock market because the conditions that provided a 9.0% annual return for your parents and grandparents will not repeat themselves during your adult lives. Even worse, many economists predict that we are due for a long-term reckoning that will make stock investments a very poor economic plan.

Although there are logical reasons to believe this, we need to keep several things in mind. First, economists who predict doom are a constant in the landscape. They’ve always been there, and with every recession, they stand up and say, “Told you so.” They tend to disappear during economic expansions.

More importantly, the fact that the positive events of the past will not recur is not a reason to conclude that new positive events – unpredictable events – will not occur that will cause a long-term stock market boom. Consider this story.

When my mother passed away in 1996, I inherited $11,000 which I put into the stock market. Four years later, it was worth $34,000 – a 32.6% annual return. Clearly, $34,000 is not, and was not then, a meaningful amount of money from the perspective of a retirement plan. The important point is the multiplicative factor. I tripled the investment in four years.

What happened in the late 1990s that allowed such a run-up in the market? One word – the internet. Half of my life was lived without the internet. Few adults alive in the mid-1990s really understood what the internet was and how it would affect our lives. Certainly, there was press about it, and we had the ability to email each other for years, but no one outside the tech world had any idea of the changes that were coming. Most people didn’t even own a laptop or a cell phone.

Our first search engines came in the mid-1990s. Yahoo was released in 1994. Competing search engines arrived at that time as well, including Netscape (1994) and Alta Vista (1995). There was even one called Ask Jeeves which arrived in 1997 (I used to use all of them). Yahoo dominated the market until Google arrived in 2000. These technologies, and the wealth they created not just for the tech companies but also for the non-tech companies that used their technology, were unforeseeable. In fact, in 1992, the stock market was coming off an abysmal period in which the 5-year compound annual growth (between 1988 and 1992) was 0.90%. That means if I had inherited that $11,000 from my mother in 1988, I would have had $11,500 in 1992. Not many people were happy with their stock market investments by the mid-1990s. If they acted on that disenchantment and withdrew their money, they would have lost a fortune.

We may be standing at a similar point in history in 2024 as we were in 1994. You all know about artificial intelligence and, according to experts, how this new technology will change human life in a far more profound way than the internet. Economies, and the stock market, grow through increases in productivity and population growth. Artificial intelligence promises to put productivity growth on steroids. Of course, there are all kinds of downsides. Can there be too much productivity growth? Can humans be replaced by machines to the point where humans become superfluous? How would we make money and buy goods and services if none of us have jobs? Also, we can always imagine the cataclysmic harm that bad actors can do with a tool as powerful as AI.

But wait. It gets better. Or maybe worse. Close behind AI is another technological revolution called quantum computing (QC). Still in a research stage (all first world governments and the largest tech companies are investing billions in quantum computing research), QC could change human life in ways that are flat out unimaginable. Before QC becomes feasible, there are challenging physics and engineering problems to solve. There is a chance that the science behind it is accurate in a theoretical sense but economically impractical. Therefore, QC could be a bust. But probably not.

If the QC engineering and physics problems get solved, then conceivably there would be another technological revolution similar to the internet and AI. QC is not bound by a binary system (i.e. the series of 0s and 1s which are strung together to form data with our current technology). Think of a binary system as having the ability to go in a straight line, either left or right. A qubit system, on which the QC computers will be based, can go in all directions simultaneously. For example, current computing can solve a maize puzzle by attempting solutions one at a time at lightning speed. QC, if it becomes a reality, will be able to attempt all solutions simultaneously instead of one at a time.

QC’s potential to solve difficult problems in all the sciences is immense. However, like AI, there are downsides. One is that QC will be able to break even the most advanced and complex computer encryptions in seconds. Every personal, corporate, government, utility, intelligence, and military IT systems could theoretically be easily accessed by a QC computer. The concept of data security will become a thing of the past.

All major governments, and most of the large tech giants are researching this technology. It is predicted that, if successful, it would become a reality by 2035, which probably means mainstream benefits (and drawbacks) would be felt between 2040 and 2050. Will these technologies affect the stock market similar to the way the internet affected the market in the late 1990s? Probably.

It is incontrovertible that the internet has given mankind enormous benefits. Because of it, I can do my job in a fraction of the time it took in 1988. However, it is also incontrovertible that the internet has caused untold harm to mankind. As a species we are a measurably less sociable animal that depends on a dopamine rush every 15 seconds. There are statistically significant increases in human depression especially in adolescents, that have been linked to internet usage. No one understands where this is leading us. It’s difficult to predict how these newer technologies will combine with the internet to affect the market after an initial surge.

So what, then, is the alternative viewpoint? The alternative to the pessimist’s view is that tax rates, interest rates, and passive investing comprise a viewpoint that is historical, inside the box, myopia. Just because we can’t lower corporate tax rates any further, and we probably will have higher interest rates for longer than we planned, doesn’t mean that corporate profitability and stock returns will be stagnant. There will always be new ways to grow, and we have every reason to believe that a new world is upon us.

Conclusion

You probably had hoped that this essay would lead to a point at which I’ll say, “therefore, you should invest your money in _________.” Unfortunately, I’m not that smart.

Why then did I write this? I wanted to convey two points:

- The conditions which allowed the average after-tax stock returns of 9.0% between 1926 and 2024 no longer exist so don’t make the blanket assumption that what happened to your parents’ stock portfolio will happen to yours.

- What conditions will affect your investments over the next 60 years? I believe that if there are history books in the 22nd century, they will say that the 21st century was dominated by two events, ranked in order of importance:

- Climate Change (its devastation, its remediation, or both)

- Technology (quantum computing and artificial intelligence)

I can answer a still valid question which is, “what would you do if you were young?” I can answer that question, not with advice, but simply with what I would do (meaning that you should form your own conclusions). I would invest money in well-researched residential real estate that is far away from coastlands, near fresh water, in what is now a cool or cold climate. The investment should be in a country that has the least political risk (countries are ranked each year on the basis of political risks, which include the rule of law, religion in government decision-making, health factors, etc.). For diversity, I would invest some of my portfolio in the dominant tech companies, like Apple, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Microsoft; also take a look at the most promising companies that are investing in QC, of which there are ten or fifteen (including those mentioned above). But be careful with real estate research. It is almost a certainty that whole swaths of real estate (both residential and commercial) throughout the world will become worthless during the 21st century. Some of this soon to be worthless real estate is currently some of the most expensive real estate on the market, like Miami, New York City, New Orleans, Mumbai, Kolkata, London, and many other coastal properties. Research before you invest.

The reason I like residential real estate is simple. They are making more people. They are making less real estate, literally. Louisiana loses land the size of a football field every hour. The City of Miami has floods in weeks when it doesn’t rain, the so-called sunshine floods. A lot of the tech people who left Palo Alto in northern California to go to Austin, Texas (the supposed new Silicon Valley) are moving back. Why? There are several reasons, but one is that they cannot bear the heat. By mid-century, mankind will be undergoing a massive migration; it might be a good idea to own the land where people will be moving.

To close out this long essay, I advise you to pretend that you’re somebody’s ancestor and do them a solid. If only your great-grandfather had the foresight to invest $1,000 in a stock portfolio for you in 1924. If only.

John J. Barton, CPA, ASA

Leave a comment